King George III was born to Frederick, Prince of Wales, and Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha in 1738. In his lifetime, western society would be challenged by rebellious colonies, shook to the foundation by a revolution in France, and profoundly distorted by repeated bouts of insanity. Through all of his personal and political struggles, King George was a popular monarch, and the people of England were loyal to him during the nation’s most trying times. His armies defeated the invincible Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, and proved to the world that constitutional monarchy was an enduring political system, outlasting the First Republic of France. In spite of his success, the reign of King George III has been a hotly debated issue among scholars, and his political decisions, particularly early in his rule, even more so.

When his father Frederick, Prince of Wales passed away in 1751, George inherited his father’s title of Duke of Edinburgh. Three weeks after his father’s passing, George the Duke of Edinburgh, was granted the title of Prince of Wales by his grandfather, King George II. Growing up, George was granted all the privileges the House of Hanover had to offer. As his father and grandfather were both born in modern Germany, George learned English and German. Indeed, in his formative years, George was a child of substantial erudition. George was particularly interested in natural science, but as a descendant of royal heritage, his tutors taught him to be a man of society. His lessons included French and mathematics, along with fencing and dancing.

In spite of his impressive educational accomplishments, George was reserved as a child. This was not helped by George’s mother, Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha. She was overbearing, and imbued the young prince with rigid moral values. Lord Bute, a close friend of George’s mother, helped George escape his shyness. Bute’s opinion was valuable to George, as Bute advised him in his personal life, as well as his political decisions. In 1756, King George II offered George residency at St. James’ Palace which George refused at the advice of Lord Bute. Again in 1759, when George was madly in love with Lady Sarah Lennox, Bute advised him against the marriage, and George begrudgingly took his advice.

But as King George II aged, it became apparent that an heir to the throne would have to be selected. If George, Prince of Wales was to be the heir apparent, he would have to learn how to overcome his inhibitions, and make meaningful decisions without the counsel of his mother, or favorite tutor. On October 25, 1760, King George II passed away, and George, Prince of Wales ascended to the throne. Now, King George III was the monarch of Great Britain and Ireland, and he would be forced to deal with the wars, religious struggles, and societal issues which plagued the empire.

In order to understand the reign of King George III, it is important to conceptualize the world prior to his ascension. The revolutionary developments of the Enlightenment, lingering religious antagonisms from the seventeenth century, and global conflict were all deciding factors in the way George governed his empire. But ultimately, he allowed his ministers to govern the empire at his advice, and this was what made him most effective. Throughout his reign, he would always share his opinion with his ministers, but in the end, he generally trusted their judgment. When commenting on the scope of the King’s involvement in government, Lord Hillsborough quoted George as asking “Well. Do you choose it should be so? Then let it be.”

When George, Prince of Wales, assumed the British throne in 1760, he inherited a troubled empire in the throes of a world war. Great Britain had been fighting a war on many fronts against a French, Austrian and Russian entente. In 1754, a skirmish at Fort Duquesne involving the Virginian George Washington sparked the conflict along the frontier in North America. But the more serious challenge to Britain came in the form of the European alliance.

Strategically, Britain leaned on the tried and tested tactic of relying on the land armies of continental European allies to do the bulk of the fighting, while the vastly superior Royal Navy would bottle up the ports of the adversary with crippling blockades. From the outset of the Seven Years’ War, Britain relied on the support of Frederick the Great of Prussia to fight in the European theatre. In spite of Prussian military prowess, Frederick had his hands full, as the Austrians, Russians and French had the Prussians vastly outnumbered.

From the outset of the Seven Years’ War, British commanders were forced to adjust their military strategy to combat the French. Having superior land forces at their disposal on the continent, and with an exposed eastern frontier, French commanders maintained a massive army on the home front to protect against hostile European powers. In doing so, King Louis XV abandoned his colonies in North America, leaving French colonists to fight off invaders.

King George II could not rely on his European army to compete with the Russian, French and Austrian forces. So instead, British commanders concentrated their armies in the North American theatre. While the British Amy ultimately proved successful in the French and Indian War, by 1759, Prussia was on the brink of collapse. For all the money the Royal Treasury poured into the Prussian State, Frederick II’s army was dwindling with each successive battle, and the Russian and Austrian armies were closing in on Berlin. To make matters worse, in 1759, French military strategists shifted their gaze from the continent to the British Isles. They amassed nearly 100,000 troops—an overwhelming force– in preparation for an invasion of Britain. French commanders planned to wait for a strong wind so they could quickly maneuver around the superior Royal Navy stationed in the English Channel.

Fortunately for the British Army, the plan never hatched. If the French made it across the Channel, they would have quickly outmaneuvered British forces, and ended the war in favor of France and her allies. Instead, on November 20, 1759, the Royal Navy caught the French fleet at Quiberon Bay, and ended all possibility of a French invasion. While this disaster was averted, it would not be the last time the French seriously considered an amphibious invasion of England. In spite of this, success in North America left Great Britain in a dominant position by the end of the war. In 1763, at the King’s request, a peace was negotiated between Great Britain and the allies that William Pitt the Elder was decidedly against. This left the British Empire with vast territorial acquisitions in North America that had to be governed and defended against future aggressors.

Unlike his grandfather and great grandfather, George III was born and raised in England. His lineage hailed from the House of Hanover in modern day Germany. The first Hanoverian to assume the throne was King George I, who inherited the throne in 1714 upon Queen Anne’s passing. While there were several Catholics who had a stronger blood connection to Queen Anne, the Act of Settlement in 1701 prohibited Catholics from assuming the throne.

From the early years of his inheritance, George I faced an underground movement that wished to restore the Stuart monarchical line which had been deposed during the English Civil War and Glorious Revolution. Supporters of the Stuart line referred to themselves as Jacobites, and the more radical elements of this movement wished to rekindle the flames of the English Civil War by reversing the tide of anti-Catholic sentiment.

In 1715, and again in 1745, the Jacobites rebelled against the authority of the House of Hanover. In 1745, Charles Edward Stuart, the “Young Pretender” was decisively defeated at the Battle of Culloden, effectively ending the Jacobite rebellions. But Catholic resentment simmered beneath the surface well into the eighteenth century. While there were English subjects who were dissatisfied with the Hanoverian monarchy, their grievances would advance from the religious to the secular realm.

By the end of the seventeenth century, European philosophers were positing new, radical ideas on government. In 1689, John Locke anonymously published the Two Treatises of Government. The Second Treatise was the most alarming to those kings who still clung to the concept of absolute monarchy. In particular, Locke’s interpretation of the social contract, or the implicit agreement between subjects and the State, called into question the divine right of kings. This laid the bedrock for the Enlightenment which followed, as philosophes of the eighteenth century took the social contract to new heights.

The Enlightenment redefined the relationship between subjects and their rulers. The Encyclopide, edited by Denis Diderot, advanced the claims of Locke, as many of the articles were aimed at advancing the theory of natural rights. The theory implied that ancient ancestors had at one point or another entered a social contract with a monarch. In other words, to join society, the individual was forced to sacrifice liberties in order to enjoy the full privileges society had to offer. Locke referred to this as the state of nature, arguing that all men are created equal by God. With regard to the social contract, Locke asserted that subjects of a king possessed the right to rebel if the State was not governed according to the consent of the people.

These ideas from the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century were truly revolutionary, and throughout his reign, King George III would have to grapple with the realization of Enlightenment ideals. American colonists drew from Locke in their justifications for rebelling against the mother country, and establishing a republic in the wake of royal authority. Less than a decade following American independence, French citizens would draw on the concepts advanced by philosophes such as Voltaire, Rousseau and Montesquieu to rebel against their royal government. The belief that all subjects possessed natural rights, and that a social contract defined their relationship to the king provided eighteenth century citizens with the intellectual fodder for revolution.

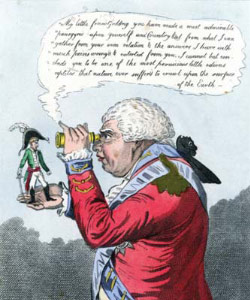

When King George III assumed the throne he still leaned heavily on the support of his tutors. Lacking political experience, George selected his tutor and mentor, John Stuart, the 3rd Earl of Bute to serve as his Prime Minister. Bute, like King George III, was politically inexperienced, but had ideas on how the British Empire should be governed. He advanced the concept of a king’s divine right to rule his people irrespective of the social contract. For this, Bute was mistrusted by Parliament and the people of England.

John Wilkes, a Member of Parliament, was the most prolific government critic of the 1760’s. On April 23, 1763, Wilkes published no. 45 of his newspaper the North Briton. In this paper, Wilkes criticized a speech delivered by King George III which applauded the Treaty of Paris that ended the Seven Years’ War. For this, Wilkes was imprisoned for libel, and when Wilkes attempted to reprint the issue he was forced into exile, leaving for France in 1764. In addition, John Horn Tooke publicized Bute’s alleged affair with the mother of King George III, the dowager Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha.

Bute could not take the pressure, and due to widespread public criticism, he resigned in 1763. Taking his place was George Grenville who immediately made efforts to reign in government spending, and collect revenue to pay for Britain’s massive debt incurred during the Seven Years’ War. Since Bute introduced the unpopular Cider Tax in England; Grenville instead looked to raise revenue from abroad. The North American colonies were an untapped source of funds–colonial legislatures only raised taxes locally to support provincial governments. Moreover, the average colonist only paid six pence in taxes per year compared with the yearly contribution of twenty five schillings from an average English taxpayer. Without much debate, the Sugar Act was passed through Parliament in 1764 as an improvement on the Molasses Act of 1733.

The Sugar Act reduced the tax of the Molasses Act from six pence per gallon, to three pence per gallon. By reducing the tax by half, Grenville believed the new act would reduce smuggling, and generate more revenue from the colonies. Instead, it did the opposite. The tax hit colonists during a period of economic recession, and while the tax was indirect, it was still felt by distilleries throughout North America. In flagrant violation of the Sugar Act, colonial merchants continued to smuggle molasses into the North American colonies from other parts of the world.

Following close on the heels of the Sugar Act was the passage of the Stamp Act in 1765. Printed goods such as legal documents, newspapers and pamphlets required a stamp in order to be valid. The King supported the passage of the Stamp Act, as did the general public. It seemed like an obvious solution: the colonies needed the British Army to protect them from their adversaries, and therefore the colonists should pay to support the British regulars stationed on the continent. The Stamp Act in no way violated the Bill of Rights passed in 1688 as part of the Revolution Settlement. Indeed, so unassuming was King George III and George Grenville that not a word passed in their correspondence about the act. Even British newspapers made little, if any mention of the Stamp Act.

In the North American colonies, news of the impending Stamp Act was met with violence. In Boston, leaders of the Loyal Nine encouraged a mob to destroy property belonging to government officials. On August 14, 1765, Thomas Crafts and Thomas Chase of the Loyal Nine hung the Stamp Master Andrew Oliver in effigy from the Liberty Tree. By noon that day, Ebenezer Mackintosh led the mob to a warehouse owned by Oliver. The mob ransacked Oliver’s property in search of the hated stamps, but turned up nothing. Later that day, the effigy of Oliver was burned in a bonfire atop Fort Hill, and shortly after, the mob attacked the residence of Andrew Oliver, not quitting until the early morning hours of August 15. Two weeks later, the house of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson met the same fate.

In England, King George and Parliament faced opposition from government officials. Edmund Burke, William Pitt the Elder and Isaac Barre all expressed their opposition to Parliament’s taxation of the colonies. It seemed impractical to collect revenue from a land over three thousand miles distant. In North America, colonists compared King George to Charles I for indiscriminately taxing the colonies without their consent. The implication was made by both parties that Britain could not keep the North American colonies in submission for much longer.

As the protests in North America intensified, Parliament continued to assert its authority over the colonies. In 1767, Lord Charles Townshend proposed to tax the colonies indirectly by placing a duty on goods such as lead, paint, glass, lead and tea. King George sanctioned the Act by royal assent on June 29, 1767 with barely a murmur of dissent in Parliament. While the people of Great Britain saw no reason why the colonists shouldn’t pay their fair share in taxes, they were aware of the corruption and mismanagement inherent in Parliament. John Wilkes, the rogue publisher of the North Briton, became the de facto leader of early Parliamentary reformers.

After returning to England from exile, John Wilkes was again imprisoned for publishing an article in the North Briton which slandered the King. As a result of his imprisonment, riots ensued in Britain. On May 10, 1768, British troops intervened by first reading the Riot Act to the mob assembled, and then the soldiers proceeded to shoot and kill six people. The event became known as the Massacre of St. George’s Fields, and this hardline approach to Parliamentary reformers would characterize the reign of King George III.

In 1780, a new wave of riots erupted with the passage of the Papists Act. Enacted in 1778, the act addressed the persecution of British Catholics that was officially sanctioned by the Popery Act of 1698. Lord George Gordon and the Protestant Association of London opposed the passage of the Papists Act. In 1780, Lord Gordon was granted an audience, and attempted to convince the king that the act would be destructive to his government, but King George was not persuaded.

On May 29, 1780, Lord Gordon called a meeting of the Protestant Association and together, they marched on the House of Commons to demand the repeal of the Papists Act. On June 2, almost 50,000 of Gordon’s followers appeared outside Westminster in support of the Protestant Association. They carried banners proclaiming “No Popery”, and wore the blue cockade of the Protestant Association in their hats. As Gordon presented the petition to the House of Commons, outside the Houses of Parliament, the ranks of the mob swelled and the protests turned violent. Members from the House of Lords, who were just arriving to take their seats in Parliament, were harassed and even physically assaulted as they tried to wade through the belligerent crowd.

The next day on June 3, the mob gathered again at Moorfields where they prepared for their next riot. That night, they attacked Newgate Prison and the Clink; allowing several inmates to escape and join the riots. The mob also vandalized the homes of several prominent Catholics and Catholic churches. By June 7, the mob was still sporadically rampaging when the British Army was summoned to quell the disturbance. When the riots ceased, 285 people were left mortally wounded.

Riots were a commonality in England before George III ascended the throne. While the Gordon Riots appeared to be motivated by a traditional fear of Catholicism; frustration over economic hardship and Parliamentary corruption contributed to the mob’s destructive nature. In England, as in Boston, Massachusetts, British subjects were beginning to expect more from their government. While a movement for Parliamentary reform still had not taken shape, resistance was simmering beneath the surface.

On March 5, 1770, Parliament repealed all of the Townshend duties save for the tax on the British East India Company tea. In response to Parliament’s resolve to uphold the tax on tea, King George remarked “there must always be one tax to keep up the right [to tax the colonies].” Tragically, on the very same day the Townshend duties were withdrawn, a series of street brawls turned into a heated altercation between soldiers of the 29th Regiment stationed in Boston, Massachusetts, and a mob that was gathering on King Street. After being pelted with rocks, brickbats, snowballs and clubs, the soldiers were finally overwhelmed. They opened fire on the crowd, and when the smoke cleared five lay mortally wounded.

The Boston Massacre galvanized the Sons of Liberty to continue the protest against Parliament’s unjust tax system. In 1773, when a shipment of East India Company tea arrived in Boston, Samuel Adams and his supports did everything in their power to send the tea back to London peacefully. However, authorities in Boston wished to uphold the law, and stood steadfast against the Sons of Liberty’s request. On December 16, 1773, hundreds of young men donned disguises, and threw three hundred and forty chests of the Crown’s tea into Boston Harbor.

At first, King George was unperturbed by the destruction of the East India teas. When John Hancock’s ship the Hayley arrived at Dover on January 19, 1774, it brought news of the patriots’ defiant act. Upon hearing the news, George remarked “I am much hurt that the instigation of bad men hath again drawn people of Boston to take such unjustifiable steps; but I trust by degrees tea will find its way to America.” The teas never did find their way to North America, and in the coming months, the tide of British public opinion would force Parliament and King George to punish the citizens of Boston for their recalcitrance.

On January 25, 1774, the Polly returned from Philadelphia with the East India Company tea onboard. The Sons of Liberty in Philadelphia and New York had bullied the consignees into agreeing to send the tea back to England before it could be landed. On January 28, London learned that Charlestown had also rejected its shipment of tea. Rather than destroy the cargo, or send it back to England, the Sons of Liberty had agreed to store the tea in a warehouse until a decision had been made on what to do with the East India Company’s product. Public opinion in England now shifted against patriots in Boston. They believed the laws of Parliament and King George III were reasonable, and that colonists should pay taxes regardless of their representation, or lack thereof in Parliament.

With public opinion on his side, King George and Parliament set out to punish Boston for the destruction of the Crown’s tea. On June 1, 1774, the first of the five Coercive Acts took effect with the enactment of the Boston Port Act. The harbor would be closed until the shipments of teas were paid for by the town. Other acts included the Massachusetts Government Act, which stripped the colony of its ability to appoint government officials. Instead, the Massachusetts Government Act granted this right to Parliament, royal governors and the King alone. The Administration of Justice Act allowed for trials to be removed from a colony if the jury was understood to be biased.

The passage of the Coercive Acts in 1774 drove a wedge between Parliament and their colonial subjects. Patriots in Boston were upset that Parliament and King George stripped them of their previously enjoyed rights. Perhaps more unnerving was the presence of four thousand British regulars in Boston. As part of the Coercive Acts, the Quartering Act guaranteed residence for the British Army. With this reality in mind, provincial militias started to gather munitions, and store them in the countryside out of reach of the British regulars. In the early morning hours of April 19, 1775, General Thomas Gage dispatched seven hundred soldiers from Boston to march on Concord, Massachusetts to stop the rebellion before it could start. In the ensuing Battles of Lexington and Concord, the British Army was forced into a chaotic retreat and by night fall, the King’s Army was back in Boston, surrounded by a force of nearly four thousand Massachusetts militiamen.

King George was now facing the threat of widespread rebellion in the North American colonies. The Continental Congress, which had been meeting since September of 1774, was debating how to supply this new provincial army and who should lead it. On June 14, 1775, the Second Continental Congress appointed George Washington to assume command of the disorganized militias that had surrounded Boston a month prior. But it was not in time. On June 17, 1775, General William Howe launched an assault on Charlestown and Breed’s Hill just north of Boston. The battle opened with a barrage from British warships stationed around the colonial entrenchments at Breed’s Hill. Taking command of the Continental Army was Israel Putnam, who ordered the militiamen to stand their ground against the assault. It would take the British regulars three frontal assaults to secure a victory at Bunker Hill.

Now, it was apparent to all that this would be a long and costly war. Following the appointment of George Washington to lead the Continental Army, the Second Continental Congress drafted a Declaration of Causes stating why it was necessary to take up armed resistance against the British Army. In addition, they assumed the role of government by issuing paper money to pay for the troops, and even assigned a committee to negotiate with foreign powers. While doing so, members of the Continental Congress still clung to the hope that there could be reconciliation between the thirteen colonies and the mother country.

In May of 1775, only weeks after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, members of the Continental Congress debated sending King George an Olive Branch Petition. John Dickinson of Pennsylvania believed that the opening of hostilities was due to a misunderstanding. Dickinson, like many of his eighteenth century contemporaries, believed that a group of wicked ministers clouded the King’s judgment, and if the colonies wrote to him directly, he might understand that it was not the fault of the North American colonists, but the English Parliament. John Adams on the other hand believed that war was inevitable, and the petition would not be well received.

Richard Penn and Arthur Lee left for England with the petition in hand, and arrived on August 21, 1775. They first met with Lord Dartmouth, the Secretary of State for the North American colonies. But their real objective was to bring the petition to King George so they could state their case. The king rejected them on the grounds that the Continental Congress was an unlawful assembly, and their dealings up to that point had been illegal.

By now, King George and Parliament had learned of the Battle of Bunker Hill, and the continued encirclement of Boston by the nascent Continental Army. But the King was more concerned with the mixed messages he was receiving from the Continental Congress. While delegates to the Continental Congress were debating the Olive Branch Petition in May, John Adams wrote a letter to a friend expressing the inevitability of war. In this letter, he suggested that the colonists should capture royal officials, and build a navy to protect the eastern seaboard. This letter was in the hands of King George only days before Arthur Lee and Richard Penn arrived in England. John Adams’ belligerent tone undermined all efforts by patriots to reach a peaceful accord with Parliament and King George III. By the time Lee and Penn were received, King George understood that all of the colonists were taking up arms against the Crown.

In response to the petition, on August 23 the king issued A Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition. The royal proclamation declared that the colonies were in a state of rebellion, and that the Crown would do its utmost to bring an end to hostilities. King George blamed the delegates of the Continental Congress stating the colonists were “misled by dangerous and ill-designing men.” Further, the king announced that the Crown will “accordingly strictly charge and command all of Our Officers as well Civil as Military; and all Our obedient and loyal subjects, to use their utmost Endeavors to withstand and suppress such rebellion.” The British government and the North American colonies were now at war.

In the early days of the conflict, the colonists struggled to wage war effectively. But in May 1775, Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold seized a retinue of canons from Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point. By March of 1776, these canons were in the hands of George Washington, who took them to Dorchester Heights overlooking Boston, and aimed them at the British force occupying the town. General Howe planned to lead a force to retake the heights, but due to bad weather, he was forced to reconsider. On March 17, General Howe and the British Army evacuated the Shawmut Peninsula, leaving Boston in the hands of the Continental Army.

In August of 1776, Howe and his force reappeared off the coast of New York. Howe planned to seize New York from the Continental Army, where he would be able to regroup, and then march his army north to meet General Burgoyne who was leading a sizeable force down from Quebec. As Burgoyne moved south through the thick brush of the countryside, he was intercepted at Saratoga, where he was decisively defeated on October 7, 1777. This victory gave the Continental Army hope, as France now joined the Americans in the War of Independence. Shortly after, Spain and the Dutch Republic joined the United States and France in their fight against the British Empire.

In spite of this King George was encouraged by Howe’s success in New York. George Washington and the Continental Army were on the retreat, and Howe’s force was numerically superior. In the winter of 1777-78, George Washington hunkered down at Valley Forge, his army on the brink of collapse. Although the British Army was vastly superior in numbers as in martial talent, Howe did not follow up his victories. In June of 1778, Washington’s Army emerged from the cold and sickness that characterized Valley Forge with a reinvigorated fighting spirit. On October 19, 1781, a Franco-American forced surrounded the British Army by land and sea at Yorktown, effectively ending any chances for a British victory in North America. In 1783, the Treaty of Paris secured a victory for the United States.

King George never fully recovered from the loss of the American colonies. In an attempt to regain control of Parliament, he appointed William Pitt the Younger as Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Exchequer after the fall of the North-Fox coalition in 1783. Pitt was only twenty four years old, but was capable of reestablishing faith in George’s constitutional monarchy. But in 1788, that faith was shaken when the King suffered a bout of insanity believed to be caused by porphyria. During this time, William Pitt and Charles Fox made the decision to install his son, the Prince of Wales, as the regent in George’s absence. In February 1789, the Regency Bill was introduced in Parliament, but before it could be passed by the House of Lords, the king miraculously recovered from his mental illness.

In the years following the American Revolution, concern shifted in Britain from the intractable colonists, to a movement for Parliamentary reform. Drawing inspiration from John Wilkes and the American Revolution, English subjects began to conceptualize a democratically elected Parliament. Since the Revolution Settlement of 1688, Parliament was understood to be a corrupt, oligarchic and nepotistic institution which was in no way representative of the people’s interest—and rightfully so. Parliament was composed men who used their money and influence to gain seats. Parliament was pieced together with rotten boroughs and pocket boroughs which, more often than not, were beholden to a Member of Parliament who through patronage, could count on their votes. Moreover, England was undergoing an industrial transformation which forced many English subjects to move to crowded cities for work. A bustling metropolis, such as Manchester, found no representation in Parliament.

While King George was aware of this when he assumed the throne, his method of ending Parliamentary corruption came from the top down. Prior to his ascension, the Hanoverians allowed factions to control Parliament and run the government. When King George III was crowned, his primary objective was to end factionalism. He did this by involving himself in the politics of Parliament, and by exercising his right to appoint and dismiss ministers who he could control. Unfortunately, this proved to be a difficult task.

Then, on July 14, 1789 the prison fortress of Bastille was stormed and taken by the Parisian mob. The French Revolution had just begun. In Britain, reformers and government officials alike rejoiced upon hearing the news. Now it appeared as though France would join the British in establishing a constitutional monarchy. At first, the revolution in France seemed to establish a constitutional monarchy similar to the British government, but then events took a radical turn. The First Coalition, led by Austria and Prussia invaded France on all fronts with the intention of restoring absolute monarchy. When the Brunswick Manifesto was read in Paris declaring the Duke of Brunswick’s intention to restore the Bourbons to the throne and punish revolutionaries, the Parisian population violently attacked prisoners in local jails. On September 5, 1792, thousands of prisoners of the revolution were massacred in the streets in what became known as the September Massacres. All hopes that France would follow Britain’s lead in establishing a constitutional monarchy were dashed.

Drawing on ideas from the Enlightenment, Maximillian Robespierre assumed de facto leadership of France in 1792 as part of the Committee of Public Safety. In order to protect France from her adversaries, radicals like Robespierre asserted that the enemies of the revolution needed to be eliminated from within. Thus the Reign of Terror commenced. Thousands of enemies of the revolution were executed by the guillotine, until Robespierre himself was decapitated by the device on July 27, 1794. But by then, France’s reputation, and respect for the ideas from the age of enlightenment had been permanently damaged.

In Britain, the Reign of Terror proved to King George III and William Pitt that democracy led to anarchy. This was a death sentence to radical reformers who sought to curtail the monarchy, and establish a republic in its wake. In their attempt to reform Parliament, John Frost and Thomas Hardy established the London Corresponding Society which spread republican ideas throughout Britain. It was widely believed that they were in contact with Robespierre’s revolutionary government, and for this reason, the Home Office placed a number of double agents in the London Corresponding Society. In 1794, King George and William Pitt believed they had enough evidence to bring the leaders of the republican society to trial for High Treason. John Thelwall, John Horne Tooke and Thomas Hardy all stood trial in the infamous Treason Trials of 1794. By the end of the long ordeal, all were acquitted. While the Treason Trials did not accomplish William Pitt’s goals of punishing dissenters, it seriously delayed the reformation of Parliament. The corruption and mismanagement of Parliament would not be reformed until 1834.

But King George and William Pitt faced a new threat. In 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte overthrew the Directory and established himself as dictator of revolutionary France. Napoleon was a brilliant general, and his success on the battlefield made him a threat to the balance of power in Europe. By 1803, Napoleon was poised to invade Britain, and showed every intention of doing so. Since Britain relied solely on her navy to defend against invasion, there was widespread fear in England that if Napoleon made the crossing, he would easily overrun British forces. To defend the homeland, volunteers came forth in record numbers. In October of 1803, King George reviewed over 27,000 volunteers at Hyde Park, and even volunteered to lead them against Napoleon should he cross the Channel.

During this time of national crisis, in 1804 the King again was overcome by insanity. But luckily, he recovered in time to learn of the defeat of Napoleon’s fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar. But by then, Napoleon had already turned the most feared army in all of Europe on the Austrians, defeating General Mack at the Battle of Ulm, and then defeating a combined force of Austrians and Russians, led by Tsar Alexander at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805. These victories, and the subsequent defeats of Prussia and Russia, left Great Britain alone in her struggle against Napoleonic France. But Napoleon’s overinflated ego would become his undoing. Invading Spain in 1808, his armies were whittled down by the guerrilla tactics employed by the Spanish peasantry. His invasion of Russia in 1812 also proved to be a disaster, leading to his subsequent defeat at the Battle of Leipzig (Battle of the Nations), and later, the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Britain played a decisive role in all of these contests. But by 1810, King George was a shell of the monarch he once was. He was no longer actively involved in politics, and when his daughter, Princess Amelia passed away in 1810, he sunk into a depression he would never recover from. Suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, virtual blindness caused by cataracts, and recurrent fits of insanity caused by porphyria; King George III willingly handed the throne to his son. In 1811, the Regency Act was passed handing over power to the Prince of Wales, who would act as Regent for the remainder of George’s life.

King George retreated to Windsor Castle where he spent his final days. In his later years, he suffered greatly from dementia, blindness and an increasing loss of hearing. On January 26, 1820, King George III drew his last breath, leaving the Prince of Wales as the heir to the throne. But as the nineteenth century dawned, the British Empire was poised for success due to the stability and leadership enjoyed under the reign of King George III.

Sign up to receive special offers, discounts and news on upcoming events.