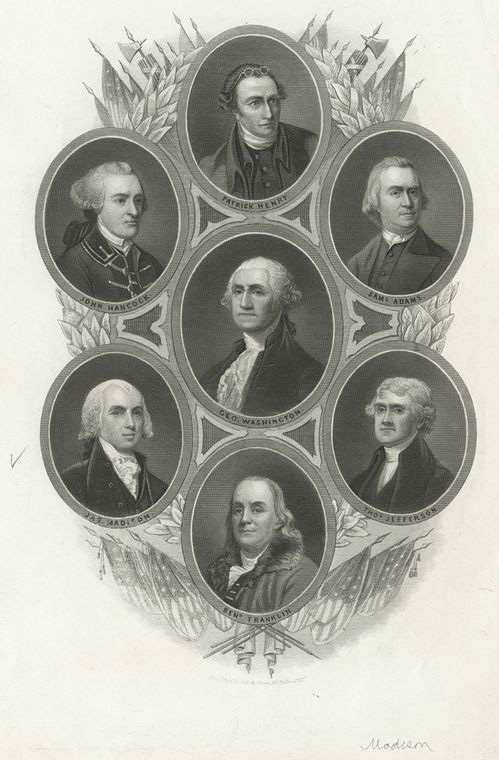

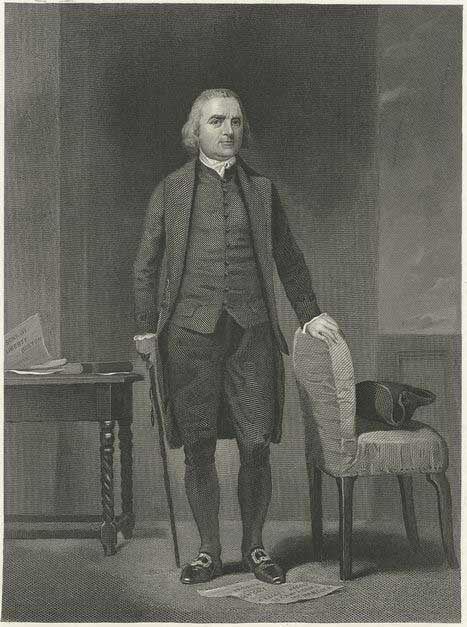

Samuel Adams was one of Boston’s most prominent revolutionary leaders. He was known for his ability to harness popular resentment against Parliament’s authority to tax the colonies in a productive manner. His role in the origins of the American War of Independence cannot be understated. His unique perspective and his ability to galvanize popular support were pivotal in the success of the Boston Tea Party.

Considered the leader of the protest movement against Parliament’s authority in Massachusetts, Samuel Adams was instrumental in convincing people to join the Sons of Liberty. As a British citizen, he often referenced the Magna Carta of 1215 which effectively ended arbitrary taxation of barons in England. In the eighteenth century, Boston’s struggle against Parliament’s Acts of taxation seemed all too familiar.

Born on September 16, 1722, Samuel Adams was born to a family which was well versed in political protest. His father, Deacon Adams, was a brewer, and owned a brewery in Boston. During the 1730’s, Boston experienced a severe economic recession due to a lack of currency, or paper money, in circulation. As a result, in 1739 Deacon Adams helped found the Land Bank which offered paper money to borrowers who mortgaged their property. This Land Bank currency was very popular, especially with poor farmers. It allowed them the power to purchase goods from Boston merchants who were in desperate need of customers. The Land Bank seemed to solve all problems; it gave farmers more purchasing power, and allowed Boston merchants to sell more goods.

Everyone did not fully support this new form of currency. The opposition was led by the Court Party, or aristocratic loyalists who sat primarily on the Governor’s Council. In 1741, the members of the Court Party used their status to pressure Parliament to outlaw the Land Bank, and the currency it produced. Those that had manufactured the currency, such as Deacon Adams, were now responsible for all of the paper money that was now circulating throughout Massachusetts Bay Colony. All of the farmers that borrowed the currency were now owed silver and gold, and this would come out of the pocket of Deacon Adams. This sent his family spiraling into bankruptcy, and even after Deacon Adams passed away, Samuel Adams would have to defend his estate from the members of the Court Party who wished to seize his land as payment for the debts Deacon Adams owed the government.

This debacle surrounding the land bank left a strong impression on Samuel Adams. This left him with a strong distrust of government. He viewed this decision by Parliament as an exercise of arbitrary power. Naturally he gravitated toward the Popular Party, which was led by James Otis Jr., a fiery orator who had personal grievances against many of the members of the aristocratic Court Party. Otis guided Adams in his young political career, and helped him develop the rhetoric, and methods of political resistance, which would be influential in the rise of the Sons of Liberty. By 1765, Samuel Adams was ready to take the lead.

In 1765, the first direct tax was imposed on the colonies by way of the Stamp Act. Samuel Adams saw this as yet another example of arbitrary authority exercised by the British Parliament. The colonies had not been consulted on issues of taxation, and moreover, they had no representatives in Parliament to defend them. Samuel Adams and the Loyal Nine led the resistance through popular protests which culminated in the Stamp Act Riots of August 1765. These riots resonated with Parliament, but they continued to pass Acts of taxation without consulting the colonies.

In 1767, the Townshend Acts were passed which taxed items such as lead, glass, paint, and tea. In response to the Townshend Acts, in February of 1768, Samuel Adams drafted the Massachusetts Circular Letter which advocated for a return to “salutary neglect” which had been enjoyed by the colonies prior to the revoking of the Massachusetts Charter in 1688. The Stamp Act Riots and the Massachusetts Circular Letter left a strong impression on Parliament, and after the riots that ensued as a result of the Liberty Affair in 1768, they were now convinced that soldiers had to be sent to Boston. On October 1, 1768, nearly two thousand British regulars landed at Long Wharf, paraded around town, and finally camped out on Boston Common.

Samuel Adams was agitated by the presence of regular soldiers in the town. He and the leading Sons of Liberty publicized accounts of the soldiers’ brutality toward the citizenry of Boston. On February 22, 1770 a dispute over non-importation boiled over into a riot. Ebenezer Richardson, a customs informer was under attack. He fired a warning shot into the crowd that had gathered outside of his home, and accidentally killed a young boy by the name of Christopher Sneider. Only a few weeks later, on March 5, 1770, a couple of brawls between rope makers on Gray’s ropewalk and a soldier looking for work, and a scuffle between an officer and a whig-maker’s apprentice, resulted in the Boston Massacre. In the years that followed, Adams did everything he could to keep the memory of the five Bostonians who were slain on King Street, and of the young boy, Christopher Sneider alive. He led an elaborate funeral procession to memorialize Sneider and the victims of the Boston Massacre. The memorials orchestrated by Samuel Adams, Dr. Joseph Warren, and Paul Revere reminded Bostonians of the unbridled authority which Parliament had exercised in the colonies. But more importantly, it kept the protest movement active at a time when Boston citizens were losing interest.

By 1773, Samuel Adams was given a new crisis to latch on to. On May 10, 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act which granted the East India Company a monopoly on the tea trade. Even with the three pence per pound tax, the tea would be cheaper than all other teas on the market in Boston. While this may have delighted some consumers, merchants that had been smuggling Dutch tea into the colonies were very upset over this new tea tax. Since the East India product would be cheaper, its arrival in Boston would undercut all of the patriot merchants who had been peddling their previously less expensive Dutch tea. To make matters worse, seven loyal merchants had been hand- picked by the East India Company tea to sell the tea in Boston. They were called the consignees, and two of them were the sons of Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson.

In the summer of 1773, news arrived in Boston of the passage of the Tea Act. Preparations for resistance were now well underway in the colonies. Samuel Adams did everything in his power to garner support from colonial merchants who would be hurt by the Tea Act. Samuel Adams started by forming the Boston Committee of Correspondence. The object of the committee was to communicate with other British North American colonies in order to share methods of resistance to taxation without representation. On October 21, 1773, Adams drafted a letter to the other colonies stating that all of the colonies would be united in their resistance to Parliament’s efforts to vend the tea in America.

By November 28, the crisis was now on the doorstep of Boston. The first tea ship to arrive was the Dartmouth owned by the Rotch family. The ship arrived with 114 crates of East India Company tea. Samuel Adams and the Sons of Liberty now had a deadline. According to customs law, the ship had only twenty days to unload its cargo. The twentieth day would be December 17, 1773. Still two more ships arrived. On December 2, the Eleanor arrived with 114 crates, and on December 15, the Beaver had joined the other two ships at Griffin’s Wharf.

Samuel Adams took the lead in negotiating with ship owners, and the customs officials for the port of Boston. On December 3, Adams ordered John Rowe, the owner of the Eleanor to unload his other cargo, but not the tea. On December 11, Adams and the Boston Committee of Correspondence ordered Francis Rotch, the owner of the Dartmouth and Beaver, to set sail for London with the East India Company tea onboard. Rotch refused to because his ships would be broadsided by two British warships, the Somerset and Boyne that were out in the harbor. Adams told Rotch that his ship must sail back to London. Adams exclaimed to Rotch “the people of Boston and the neighboring towns absolutely require and expect it.”

Now there were only a few days before the cargo of tea had to be unloaded according to customs law. On December 14, Samuel Adams brought Francis Rotch to the customs collector to ask for clearance for his ships to leave the port of Boston. The customs collector stubbornly insisted that no law would allow the ship to leave before unloading the tea. Two days later, on December 16, Rotch appeared at Old South Meeting House before thousands of angry Bostonians. Samuel Adams advised him to appeal to Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson for permission to send his ships back to London. Francis Rotch reluctantly straddled his horse, and made his way to Milton where the Royal Governor was staying at his summer estate.

After hours of uncertainty, and anxious waiting at Old South Meeting House, Francis Rotch finally reappeared with the Governor’s decision. Rotch nervously announced that Hutchinson had refused his request that the tea had to be brought into Boston before his ships could depart. If Rotch attempted to leave, the two British warships and the canons from Castle William would blow his ships out of the water. After all of these attempts, Rotch now refused to take action. Samuel Adams rose from his pew, and announced, “This meeting can do nothing more to save the country!”

Historians cannot be certain, but many believe that this statement by Adams was a signal to the Sons of Liberty waiting outside to destroy the tea. While Adams did not participate in the destruction of the tea, he stayed behind at Old South Meeting House along with other patriot leaders to provide a distraction to the British Army stationed in Boston. Although he did not wield a hatchet, or don a Mohawk disguise, he was instrumental in securing support and sympathy from other British North American colonies. The very next day, on December 17, Adams wrote letters to the Sons of Liberty in New York and Philadelphia proudly announcing how peaceful the destruction of the tea was.

Samuel Adams’ role in resisting taxation without representation culminated with the destruction of the tea. In his efforts to see the tea sent back to London, Samuel Adams made every effort to appear as though he, and the Sons of Liberty, were lawfully opposing the landing of the cargo. In a letter to Arthur Lee, Adams laid the blame on the consignees. “The consignees, together with the customs collector, and the governor of this province [Hutchinson],” were responsible for the loss of the tea because of their refusal to negotiate with the people of Boston.

His skillfulness to use the weakness of customs law to his advantage, and his ability to galvanize popular support for the cause which he believed in, solidified his place as a leader among leaders in the cause for liberty.

Sign up to receive special offers, discounts and news on upcoming events.